Rana Plaza: Eleven years on, what has changed?

Eleven years ago today, I was stuck in Dhaka traffic, mindlessly scrolling through my phone, when my social media newsfeed exploded with images of chaos and destruction. A massive pile of rubble and debris, with people shouting and screaming in horror. Later, this event became known as ‘the Rana Plaza disaster’ and remains, to this day, one of the deadliest industrial accidents in history. On April 24, 2013, the eight-storey Rana Plaza building, where nearly 5,000 garment workers worked, collapsed in just 90 seconds.

I will never forget the moment I first learned the news. I felt frozen, my heart racing as I tried to comprehend the scale of the tragedy unfolding so close to home. Frantically searching for information about which building Rana Plaza was, I wondered if I knew anyone who worked there. Did any of my friends or acquaintances have businesses in the building? The shock was overwhelming, and I knew this moment would stay with me forever.

As the days and weeks passed, the full extent of the tragedy became clear. The world watched in horror as the death toll continued to rise. But even as the initial shock faded, the memory of that moment remained seared in my mind. It was a wake-up call, a reminder that pursuing profit at any cost can have deadly consequences. Eleven years later, I remain firmly convinced that we all have a responsibility to demand better working conditions and safety standards for those who produce the goods we consume.

The Rana Plaza disaster was a tragedy that claimed the lives of at least 1,134 garment workers, most of them young women, and injured more than 2,500 more. Yet amidst the horror and devastation, incredible bravery and resilience emerged. Like Reshma Begum, who was trapped in the rubble for 17 days before being rescued. The photo of the moment they found her, showing her buried in the debris with an arm reaching out, became a symbol of hope and survival amid unspeakable tragedy.

Moments of heartbreak also emerged from the rubble. Like the photo of Shima Akhter and Shahidul Islam hugging each other in the wreckage of the collapsed building. Their embrace, captured in a single frame, speaks to the deep bonds of friendship and community that existed among the workers who perished in the disaster.

These photos were widely circulated in the aftermath, and served as a powerful reminder of the human cost of the global garment industry's negligence. However, the question still remains: Did these images and the tragedy as a whole make any lasting change in the mindset of the industry?

In 2023, Shahidul Islam was beaten to death for his labour rights activism to help workers collect their due bonuses and wages from a factory in Gazipur, a major garment industry hub on the outskirts of Dhaka, Bangladesh. This horrific incident raises a resounding call for justice and demand for unwavering safety of workers, union members and human rights defenders.

Garment workers in Bangladesh continue to work under poor working conditions and wages. During the minimum wage negotiation period in Bangladesh last year, many fashion companies failed to support worker and union demand for fair wages. This period unfolded in a challenging environment where a garment factory worker, Rasel Howlader, was shot dead by the police with several labour organizers unjustly arrested and injured.

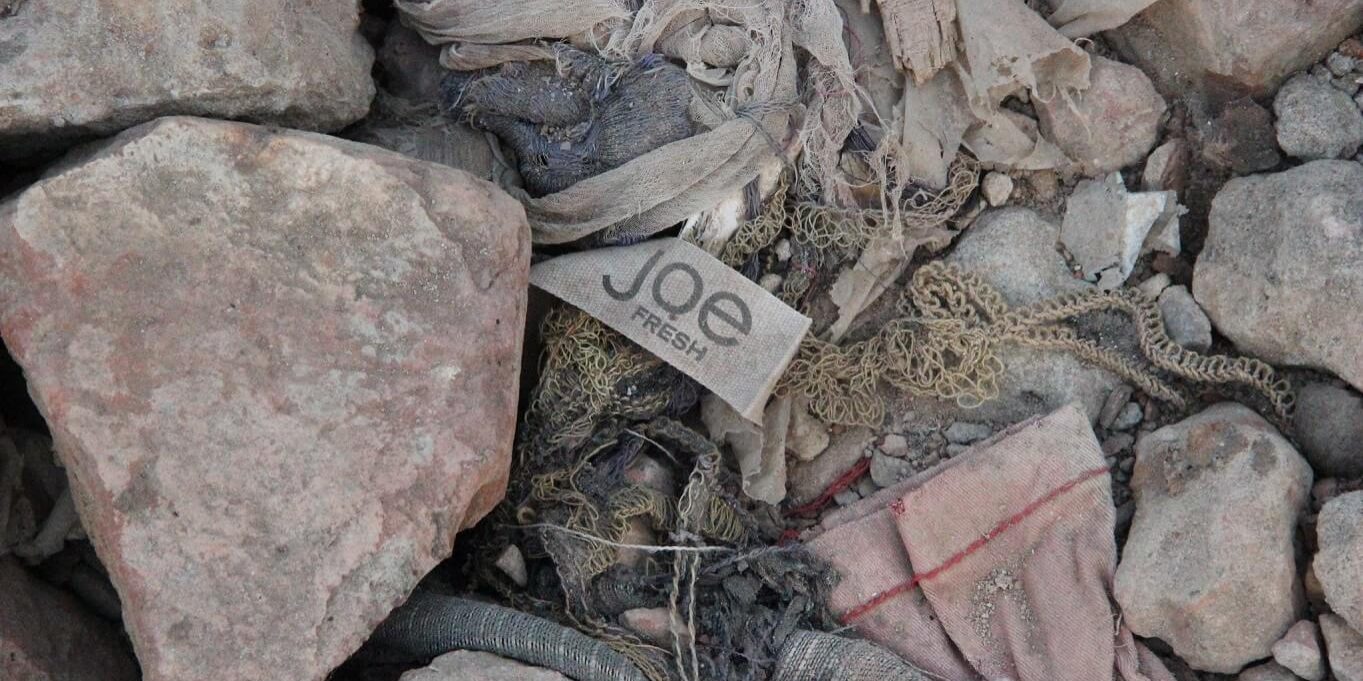

Eleven years on, some progress has been made. Companies have been pressured to sign the Bangladesh Fire and Building Safety Accord, an independent agreement designed to make all garment factories in Bangladesh safe workplaces. Since 2013, more than 160 companies have signed the Accord, including

Loblaw (Joe Fresh), a major Canadian garment producer.

Joe Fresh is the only Canadian brand to sign the new International Accord in 2023, while other Canadian companies are completely absent from the list of signatories.

Furthermore, the absence of commitments to pay a living wage from these companies is concerning.

However, there is still much work to be done. The legacy of Rana Plaza is a stark reminder that the human cost of fast fashion and exploitative labour practices cannot be ignored. It's up to us as consumers, activists, and members of the global community to demand accountability and push for change. Only then can we truly honour the memory of those who lost their lives in this preventable tragedy.

With this in mind, I am proud to pledge my support to the What She Makes campaign, which holds Canadian fashion brands to account for not paying the women who make our clothes a living wage.

Did you know that …

- The global fashion industry generates $2.5 trillion annually, but garment workers typically earn less than $6 a day.

- In 2013, the year of the Rana Plaza disaster, Bangladesh was the second-largest exporter of apparel in the world, with the garment industry accounting for 80% of the country's total export earnings.

- It is estimated that approximately 1 in 6 people worldwide work in the global fashion industry, with most workers living in developing countries with little to no labour protections.

These statistics highlight the damaging social impact of the fast fashion industry and the exploitation of workers in developing countries who produce the clothes that we wear every day. The Rana Plaza disaster was a tragic example of the consequences of prioritizing profit over worker safety and the need for systemic change in the fashion industry.

Visit WhatSheMakes.ca to add your name to the growing list of Canadians demanding big clothing brands pay the women who make our clothes a living wage, enabling them to afford a decent standard of living for themselves and their families.

Shamminaz Polen is a Manager of International Programs at Oxfam Canada.

Nirvana Mujtaba, Women's Rights Policy and Advocacy Specialist at Oxfam Canada, provided facts and figures.